Photo by Alonso Reyes on Unsplash

Previously we looked at the methionine cycle, one of the functions of which is to generate methylation capacity Vitamin U (S-methylmethionine) information: The methionine cycle and Vitamin U Here we'll take a closer look at methylation.

Methionine is an essential amino acid found in protein. When methionine is remade from homocysteine, there are three nutrients that can supply the methyl group -

1) Folate/Serine

2) Choline/Betaine

3) Vitamin U

Remethylation is catalyzed by a specific enzyme for each nutrient -

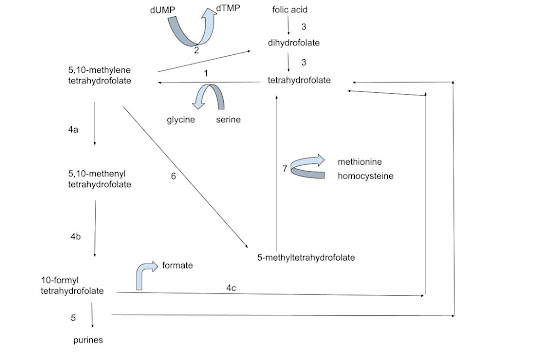

1) Methionine synthase (MS) uses the cofactor B12 to transfer a methyl group from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (folate) to homocysteine to form methionine and tetrahydrofolate.

2) Betaine homocysteine methyltransferase 1 (BHMT1) uses the cofactor zinc to transfer a methyl group from betaine to homocysteine to form methionine and dimethylglycine.

3) Betaine homocysteine methyltransferase 2 (BHMT2) uses the cofactor zinc to transfer a methyl group from Vitamin U to homocysteine to form two molecules of methionine.

We get most of our folate from vegetables and whole grains. Folate comes in various forms which our body converts into the active form MTHF. In fact, the major source of folate for many Westerners is folic acid added to processed wheat flour to make up for the loss of folate during milling. While a certain amount of folate we eat is already methylated, the main role of folate is that of a carrier. The same folate molecule accepts and donates a methyl group many times during its existence. The methyl group is supplied several enzymatic steps upstream by serine.

Betaine is abundant in whole grains. It functions as an osmoprotectant to the plant, so is found in most grains with the notable exception of rice, most of which is grown underwater. The major source of betaine in the typical American diet is bread, especially whole grain. In addition, a substantial amount of betaine is derived from choline. Choline is found in most whole foods, especially eggs, meat and whole vegetables. It is mainly used in phosphatidylcholine synthesis. Extra choline is broken down to make betaine.

Betaine has three methyl units available that can feed into methylation pathways at various points. Betaine donates a methyl unit to homocysteine to produce methionine and dimethylglycine in a reaction catalyzed by betaine homocysteine methyltransferase. Dimethylglycine donates a methyl unit to tetrahydrofolate to produce sarcosine (methylglycine) and methylenetetrahydrofolate in a reaction catalyzed by dimethylglycine dehydrogenase. Sarcosine also donates a methyl unit to tetrahydrofolate to produce methylenetetrahydrofolate, this time in a reaction catalyzed by sarcosine dehydrogenase. The latter two reactions activate folate, which enables it to methylate homocysteine.

Vitamin U (S-methylmethionine) from plants has two methyl units to donate as its reaction with homocysteine not only converts homocysteine into methionine, but itself is transformed into a second molecule of methionine. The reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme BHMT2 and mostly happens in the liver and kidneys. The major dietary source of Vitamin U are fresh vegetables and fruit.

Does Vitamin U contribute to methylation status in people? Assuming a maximum of 250 mg Vitamin U is taken each day from the diet (from a generous one liter of cabbage juice), that's 1.25 mmoles of Vitamin U or 2.5 mmoles of methyl groups. In a typical diet, methionine contributes 10 mmoles, choline contributes 30 mmoles, betaine contributes 26-75 mmoles, and folate (via methylneogenesis) contributes 5-10 mmoles of methyl groups per day. Assuming these estimates are correct, Vitamin U plays quite a modest role in the methylation status of people. However, it should be taken into consideration that not all of these nutrients give up their methyl groups. Methionine incorporated into proteins and choline used to make phosphotidylcholine are examples.

For a vegan with a low protein diet and whose staple grain is rice, the contribution from Vitamin U is more significant as a percentage, though this diet may be low in total methylation capacity. It's not that Vitamin U is not a quality source of methyl groups - it's just that it's low in abundance in a natural diet compared to the other methyl donors. The fact that mammals have an enzyme devoted to its use demonstrates the importance Vitamin U has in the diet. To increase the contribution of Vitamin U towards methylation in people whose diet contain low concentrations of methyl groups, it is possible that larger amounts of Vitamin U via supplementation could be effective.

References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17209172

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23196816

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23661599

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17413090

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1128236